Share this

The Rise of the Invisible Bank

by TPG Software on Apr 13, 2023

Digital banking technologies — including artificial intelligence, analytics, personal financial management software, internet of things, voice banking, banking as a service and fintech innovation — are converging toward one end goal: invisible banking.

This is banking you don’t have to think about. You tap to pay. You drive out of a parking lot and the car pays the parking fee. You tell the bank you’re saving for your daughter’s college tuition and money is automatically moved from your checking account to a special tuition savings account at appropriate intervals. You’re offered a loan or a discount at the moment you need it, at the time you’re making a purchase.

In five years, banking will be behind the scenes, embedded in everyday activities.

“You want to get all the hassle away, so banking is becoming invisible,” said Benoit Legrand, chief innovation officer at ING.

That change will not be overnight, but the seeds of it are already sprouting in a number of different areas:

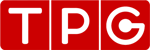

Internet of things

The internet of things has long been promised as the next tech breakthrough, although many efforts — such as Google Glass — have fallen short. Yet wearable devices appear to be gaining ground again (Amazon is launching its own version of tech-enabled eyewear that can access Alexa along with a ring that does the same), and promise to make banking and money movement seamless.

By 2025, Alan McIntyre, senior managing director for banking at Accenture, expects payments to move completely away from cards and phones toward wearables and biometrics.

“Whether it is tapping a ring that you wear or facial recognition, the payment will become more seamless,” he said. “The idea of taking the card out of the wallet will seem archaic. What you think of as transactional banking will disappear.”

Source: https://ipropertymanagement.com/iot-statistics

Source: https://ipropertymanagement.com/iot-statistics

An ING startup initiative, FINN-Banking of Things, develops software that lets smart devices make autonomous payments on behalf of the user.

It can be embedded in smart bottles, so that when a bottle is close to empty, it reorders. It can be installed in a car, so that at a gas station or tollbooth, the payment is made automatically.

“You can load your car with 100 euros or dollars and the car pays whenever it’s put in those conditions,” Legrand said. The bank has been piloting the technology with BMW.

NS, the public transportation system in the Netherlands, uses this technology for invisible tickets.

“You walk in, we know where you are, where you entered, on which train you stepped in and where you stepped out, and you’re charged for your trip automatically,” Legrand said. “This is what you want.”

Voice banking

Alongside those changes with wearable tech, payments, on-demand loans, and other banking activities will increasingly be done by talking to Siri, Alexa, or a car or phone app.

“When you think about the world and how we’ll access banking services, we’ll talk to Alexa and Siri and get financial information,” said Brett King, futurist, author and founder of Moven. “We might use smart glasses from Facebook and Apple. Those operating systems will be the gatekeepers for the way we connect to core banking utility.”

King has long espoused the idea of one digital assistant to rule them all. The virtual assistant providers have started to show a willingness to interoperate. In late December, Amazon, Apple, Google, and Zigbee Alliance formed a working group to develop an open standard for smart home devices.

Legrand calls banking via Alexa, Google Home, Siri and the like “bionic banking.”

“Voice banking through these machines is where we are going,” he said. “Why? Because human beings are lazy. First we needed to go to the bank to get cash. Now you can open your computer and do a couple of things, you can tap your phone and pay. The next stage is to say Alexa, transfer two euros to my mom. This is the next step in laziness.”

But Legrand also warns that as people become more reliant on this autonomous, invisible technology, it has to work reliably and there has to be strong customer service. A customer won’t be willing to wait 25 minutes for a payment gate to open.

“You need to have someone on the line to help you,” Legrand said. “The more digital we are, the more human touch we will need. You subcontract a lot to machines, which is fine, but when there’s a hiccup, you want to have someone to unlock situations fast. It’s a bit like oxygen: You don’t realize you’re using it until you stop having it. The moment it stops, someone needs to give you oxygen very rapidly.”

McIntyre also sees a place for in-person conversations five years from now.

“Our research suggests that still the majority of people want to be able to do that navigation with human beings,” he said. “There's still a lot people that when they're making bigger decisions want the reassurance of having a human being talking to them.”

Financial wellness

The personal financial management aspect of digital banking also appears on track to be more seamless and effortless in five years.

Kristen Berman, a behavioral scientist and co-founder of Irrational Labs and Common Cents Lab, a Duke University initiative dedicated to improving the financial well-being for low- to middle-income Americans, said that the overarching trends in money have had mixed results for financial wellness.

“It’s wonderful for people to have access to money, and decreasing the amount of time ACH payments will take us is good,” she said.

At the same time, it’s easier for people to rapidly spend the money in their accounts, she said.

To cope with this, many PFM or financial wellness apps try to show people where their money is going through visuals like pie charts and traffic lights, so they can start to see where they might be spending too much on going out to dinner or on coffee at Starbucks.

These spending views rely on accurate categorization, which is not always a given.

“I always joke, we can put a satellite in space … but we can’t get our transactions categorized correctly,” Berman said. “Transfers are still being categorized as spending in apps, which makes people not trust these types of apps to give you insights, which makes this useless. No kidding people aren’t taking action. We don’t trust the insights that we’re being given.”

Berman sees this going in two possible directions. Either the technology gets better and people start to trust it or consumers are given the tools to make better decisions using heuristics and a lot of the work is done for them.

She would prefer the latter: Instead of presenting people with categorizations and hoping they form better habits because of it, the customer is helped to make changes.

For instance, a customer could sign up for a goal, such as taking a vacation at the end of the year, and the bank would make automatic deductions from their checking account to a vacation account, based on their income and expenses. A few fintechs and banks offer such automated savings tools already, including Digit, Chime, Qapital, Acorns, Fifth Third and Bank of America.

“I would love a behavioral economics method that would help people to do this,” Berman said.

McIntyre of Accenture said that in five years, banks will be giving consumers more in-the-moment advice on things like which payment mechanism to use, who to pay when, how to split payments. Such small decisions can add up to financial wellness.

U.S. Bank and Huntington Bank are already experimenting with this, using technology from Personetics. Bank of America’s Erica virtual assistant also is beginning to provide this type of advice.

The overall idea is to stop customers from making bad decisions that are not in their financial self-interest. Fintechs like Chime and MoneyLion already tout the idea that they protect consumers from bank fees.

Ultimately, banks’ improvement in this area will hurt their ability to make fee income, but if they do not improve, they risk losing further business to fintech upstarts.

“The U.S. banking industry still has tens of billions of dollars of insufficient-funds fees and we're getting to a point where technology should save customers from that,” McIntyre said. “The challenge is going to be self-cannibalization for the bank. The banks have benefited from customers making suboptimal decisions.”

Some banks have already attempted charging monthly maintenance fees. Monzo, the popular U.K. challenger bank with 4 million customers, recently tried that. But customers balked.

Another way banks could make up for lost fee income is they attempt to disintermediate other industries like telecommunications by using the visibility they have into customers’ spending patterns to help them get better deals. For instance, a bank could see that a customer is leasing an 18-month-old Toyota Sienna when they could lease or buy a new car with lower monthly payments elsewhere, and thus disrupt auto dealers.

U.S. banks are gingerly starting down this path. Wells Fargo’s Control Tower, for instance, gives customers the ability to see all their recurring monthly payments.

The next generation of this idea is to actually help people switch to cheaper providers, whether they’re auto dealerships, mobile service companies, or other firms.

For example, ING has a personal financial management app called Yolt that’s used by a million customers in the U.K., France, and Italy. ING crunches the customer data it gathers in Yolt to help users make better decisions about the products and services they buy. It will tell them which utility providers could give them a less expensive service, and help them switch.

“We have always a challenger’s mindset,” said Legrand. “For us, this is an enormous opportunity to expand, to give new services, innovate, and better service customers.”

Banking as a service, APIs and fintech partnerships

For years, banks and fintechs have sparred over control of customer data, with each side blaming the other as either purposely holding up sharing to keep a competitive advantage or encouraging customers to engage in unsafe behavior to allow access to bank accounts.

But banks and fintechs are increasingly using application programming interfaces to share information.

Banks are also striking deals with companies to offer banking-as-a-service, which can allow third parties to offer banking products without actually becoming a bank.

Phillip Rosen, CEO of the fintech Even Financial, said that such interactions are the hallmark of the future in which banking becomes embedded in other activities.

Even Financial has a network that connects about 40 financial services firms, including Marcus by Goldman Sachs, American Express, nbkc bank, Social Finance, LendingClub, Prosper, Upgrade and Avant, with consumer sites like the Penny Hoarder, the SmartWallet and ClarityMoney through APIs. Consumers searching for a product not only get an offer suitable to them; they can fully apply for the product right then and there.

Rosen envisions the embedding of banking in multiple places, the same way apps have become interoperable that used to operate independently.

“Now you go to your phone and if you have something scheduled on your calendar, you're probably going to see a notification saying here's the shortest route or there's traffic,” Rosen said.

BBVA, meanwhile, has been actively engaging in offering banking as a service, and expects to see those efforts grow. The bank is working with retailers to embed its services, like quick online loans, in their websites at the point of checkout.

For example, the bank might offer short-term loans through Target. The customer may believe the loan comes from the retailer, not BBVA.

But in an interview earlier this year, Javier Rodriguez Soler, the chief executive of BBVA USA, said he’s comfortable with the bank being invisible in that transaction. The customer may believe the loan comes from the retailer, not BBVA.

“As long as this customer receives a good loan, and we are helping, I don’t mind if he believes Target is giving him the loan,” he said.

Link to Original Article: The Rise of the Invisible Bank